| Past Issues in this Series |

|

Fat Pads, Posts, and the

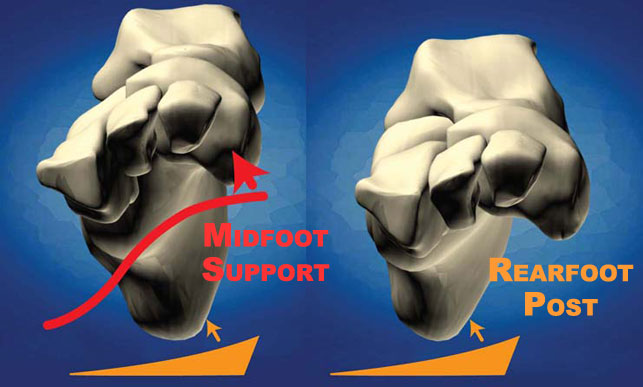

"Tarsal Shelf" By Edward Glaser, DPM Let’s say we had a ball of bread dough, and for some reason we wanted that ball to tilt towards one side or the other. Let’s say we put a wedge under one side of it to do this. Instead of an observable tilt, we would watch the dough slough down off the wedge and puddle onto the table. For two reasons: lack of rigidity in the dough and the natural tendency of a round object to roll down hill. This is analogous to what we are trying to do to the heel with a rearfoot-posted orthotic. The bottom of the calcaneus is rounded and it sits on a fluid-filled bursa and one of the largest fat pads in the body. Did we really think we would significantly affect the position of the rearfoot with this strategy? What kind of leverage can we expect from an average 4° post, working through fat, on a rounded object? Is there really enough time at heel strike to effectively control pronation? With such soft mechanics? And with the heel off the ground at heel lift? I don’t have the exact data, but I can make a very reasonable guess about the amount of effective force this strategy can deliver: something just above none and not nearly enough to change the posture and function of the weight-bearing foot. Well, how about a 10° post? See below what effect a 10° wedge did for that flexible flat foot. For an explanation I refer you to our dough example above.

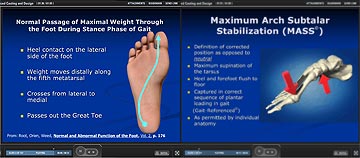

The next problem we encounter with posting strategy is after heel strike. If we followed the classic slipper casting technique, we captured a 50% pronated subtalar joint (neutral) and a maximally pronated midfoot (lifting rays 4 and 5). Then the lab we sent it to “cast corrected” the arch down some more. And that is as much help as our patient’s foot can expect to keep the arch up at midstance. If that foot is typical of most of us, that arch is flattening too much. Now it has to find the necessary resources to re-supinate from a mechanically disadvantaged position. Yes, the windlass effect of the plantar fascia and leg external rotation are trying to help. But if that was all it took for the average foot to re-supinate, why do we observe the marked prevalence of flat, flexible feet and the consequences of walking on unlocked first rays? See the diagram showing changes in re-supination forces with arch height from my last article. Finally, our posting/low-arch strategy completely breaks down with heel lift. If we haven’t controlled enough pronation at midstance (while the rearfoot is still on the ground and theoretically responsive to a post), there is definitely nothing more to add once the heel leaves the ground. The post is no longer making firm contact with the heel so it is out of the loop. We have been taught for so long to avoid full arch support that we have managed to also avoid crucial corrective forces during heel lift. The latter point is very ironic when one considers the MASS position correction alternative. The MASS strategy puts its focus on full and firm arch support. Consider the frontal plane sections of the foot bones below. From a leverage standpoint alone, the difference is outstanding. Again, without gathering actual data, some very reasonable assumptions can be made. With a medial post angling slightly upwards into the fat pad of the heel and pushing close to the pivot point of the heel, we can expect very little torque for correction. But if we put an entire shelf of support under the tarsus, shaped identically to the foot in MASS position, we get extremely good leverage over a wide surface area. The foot is not allowed to develop more than minimal downward momentum into pronation and the shell acts as a loaded spring to firmly re-supinate the foot. The calibrated flex of the shell is the key to getting the right level of comfortable support for any given foot.

|