|

|

|

Jarrod Shapiro, DPM

Practice Perfect Editor

Assistant Professor,

Dept. of Podiatric Medicine,

Surgery & Biomechanics

College of Podiatric Medicine

Western University of

Health Sciences,

St, Pomona, CA |

(Part 2):

In last week's Practice Perfect I introduced the historical fact that the Silfverskiold test for ankle equinus was not created to evaluate the common disorders we typically see but rather to evaluate spastic equinus. I also questioned our current use of this test due to its original intent for something other than what we commonly apply it. I was bold enough to suggest – perhaps foolish is the more appropriate term – that if one read Dr. Silfverskiold's original article they would find that his discussion actually undermines the basic concepts we use today. With that statement in mind, I'd like to discuss this idea further.

|

Part 1 Recap: The Silfverskiold test demonstrating a gastrocnemius equinus. |

|

To understand my criticism, however, some prior discussion of the concepts Dr. Silfverskiold establishes in his paper is required. I urge our readers to hang in with this biomechanical discussion. It's very interesting and (hopefully) thought provoking.

Dr. Silfverskiold spends a significant amount of time discussing certain concepts that lead up to his test. It is these very concepts and how they explain the test that lead to my questioning the validity of our use of the Silfverskiold test for non-spastic patients.

First, he discusses the "transmission effect." In this situation the movement of one joint is transmitted to other joints via a "many joint" muscle. A "many joint" muscle is any muscle that crosses two or more joints. He uses the gastrocnemius muscle as an example. The gastrocnemius is actually a three joint muscle because it crosses the knee, ankle and the subtalar joint. Of course, there are many potential examples of these "many joint" muscles, but let's stick with the gastrocnemius for brevity's sake.

The next obvious question then is, "how does this transmission effect occur?" Dr. Silfverskiold describes the mechanism via "active insufficiency," which occurs during active use of the muscle. This is a functional loss of muscle strength due to the tension of the muscle being used up by the first joint. For example, if you extend the knee it becomes harder to dorsiflex the foot. You can prove this to yourself by extending your knee until your leg is straightened and then attempting to bring your toes toward your body in an upward motion. It will be more difficult to do this while your knee is extended rather than if your knee is flexed. This motion utilizes active insufficiency of the gastrocnemius muscle, reducing the available dorsiflexion by essentially using up the available muscle fiber length. If you, the physician, move the various joints of the lower extremity on your patient, you would be engaging in "passive insufficiency" since the patient is not actively firing the muscle. This passive insufficiency is what we implement during the Silfverskiold test.

Dr. Silfverskiold then goes on to apply these concepts to patients with neurological disorders in which spasticity is present. Spasticity, he argues, leads to a worsened and earlier appearance of muscular passive (and active, I might add) insufficiency. Think of the patient with spastic diplegia as a result of spastic cerebral palsy. These patients toe-walk and, in some cases, cross their legs over each other (scissoring). This is due to the excessive activity of the hip adductors and triceps surae. The more spasticity present, the greater the incidence of toe-walking. As explained by Dr. Silfverskiold, spasticity leads to an earlier presentation of passive insufficiency in the gait cycle.

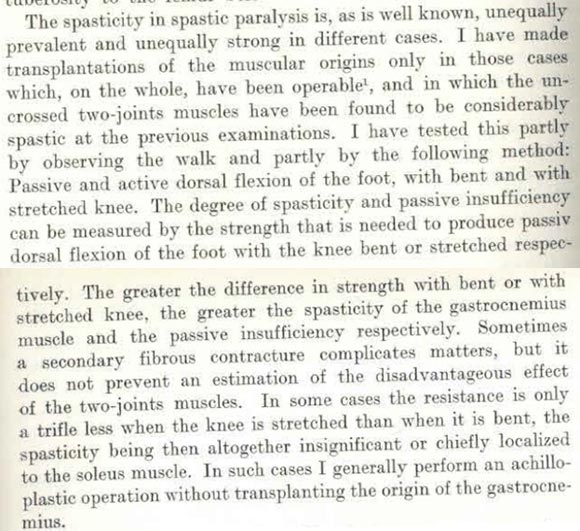

Now, with this information in mind, read the description in Figure 1 taken directly from Silfverskiold's article.

Figure 1: Original description of the Silfverskiold test. |

|

The excerpt above beautifully describes the Silfverskiold test as well as accurately reflects our current method of choosing a tendo-achilles lengthening procedure for a combined gastrocnemius-soleus equinus and the gastrocnemius recession for an isolated gastrocnemius equinus.

Dr. Silfverskiold does not at any point apply this to non-spastic conditions. He uses this only to differentiate the relative amount of spasticity of his patients, and, like us, uses the test to choose his procedures.

Nothing earthshattering yet, right? You can buy my argument that we're using the test for something different than what it was originally intended. We clearly need more research to validate the test for use in non-spastic patients.

However, it's his discussion about passive muscle insufficiency that really calls into question the basic premise of this test for non-spastic patients. You see, he explains that passive insufficiency is a normal physiologic parameter of muscles that cross more than one joint. If he's correct then our use of the Silfverskiold test just doesn't make sense! Of course, a patient will have a gastrocnemius equinus if the knee is extended when you dorsiflex the foot as this represents the normal passive insufficiency of the muscle. This test just might be completely useless for us! We're just testing normal muscle anatomy, not something pathological. This is the non-pathological transmission effect in practice.

In my short 6 years of practice I've done a lot of physical examinations, which have included checking for equinus. In the vast majority of patients, I have found a gastrocnemius equinus. I've also examined a fair number of young, mostly healthy students without pedal complaints, and many of them have equinus. If it turns out that the vast majority of our population has a particular finding is it not at all possible that the finding might just be normal?

No wonder there's controversy about ankle equinus. Even our national speakers argue about the difficulty with measurement and the inability to find consensus on the very definition of equinus. Since our most basic examination technique was initially meant for a different patient population, we may be measuring normal function and calling it abnormal. It's no wonder there's controversy.

I know what you're thinking; we treat equinus as a major component in so many conditions (diabetic foot ulcers, plantar fasciitis, metatarsalgia, adult acquired flatfoot, etc.) and we get good results. This has to be a significant component of these disorders. We could talk about each one separately, but I'll explain the entire lot using Silfverskiold's theories. When we do a posterior muscle group lengthening procedure or utilize a non-surgical stretching method (e.g., calf stretching or night splint) we are either reducing the passive muscle insufficiency (non-surgical methods) or weakening the muscle itself (surgery). Both of these methods reduce plantar foot pressures and rotational forces around the subtalar joint, thereby reducing the contribution of a (possibly) normal calf muscle to the disease.

Additionally, if you consider the number of treatments actually applied to patients for a particular disorder one can reason it was one of the other methods that treated the problem rather than "fixing" the equinus component. For example, how many flatfoot reconstructions do you do with isolated gastrocnemius recessions? Few to none, right? Many of these surgeries combine multiple procedures to repair the problem foot. Which is actually fixing the problem? It's impossible to know.

I believe this idea may have significant ramifications for both future research and clinical practice. Of course I could also be barking up the completely wrong tree. What do you think?

Best wishes.

Jarrod Shapiro, DPM

PRESENT Practice Perfect Editor

[email protected]

REFERENCE:

Silfverskiöld N. Reduction of the uncrossed two-joints muscles of the leg to one-joint muscles in spastic conditions. Acta Chirugica Scandivica. 1924; 56: 315-328.

Get a steady stream of all the NEW PRESENT Podiatry

eLearning by becoming our Face book Fan.

Effective eL earning and a Colleague Network await you. |

|

|

This ezine was made possible through the support of our sponsors: |

Grand Sponsor |

|

|

| Diamond Sponsor |

|

|

| |

Major Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|