Practice Perfect 833

Making Practice Perfect Decisions

Part 10 - Break Other Rules When Necessary

Making Practice Perfect Decisions

Part 10 - Break Other Rules When Necessary

We’ve made it to number ten of our Making Practice Perfect Decisions series. The decennial, the denary, the decuple, the decagonal. Yes, it’s the final principle of our series. Today is about breaking the rules. Because sometimes you just have to defy, disobey, disagree. Sometimes you have to be flexible, especially when working with patients. Not every patient will benefit from a rigid adherence to the nine principles we previously discussed. Today, you have to…

One of the marks of an expert is the ability to judge when veering off the beaten path will benefit the patient. Unfortunately, that type of expertise usually comes because of making a bunch of poor decisions over the years. I’ve made my share, I’m sure. Now, there’s no way to make a rule out of breaking the rules, as in “here’s when to decide to deviate from the well-worn pathway,” but, I think, even here we can be a little analytical.

First, violating some of our other principles to benefit the patient doesn’t mean you should violate all of them. In fact, harkening all the way back to our first three rules, I assert that these really are inviolable. Here they are again as a quick review.

Yes, these three principles are the sine qua non of decision-making in podiatric medicine and surgery. Without these three principles, nothing remains to guide us. It’s a free-for-all, a struggle, a scuffle, a scrap, a fracas!

Ok, sorry, getting a little carried away.

These three principles are the gravity of decision-making, grounding us to the earth of thoughtfulness and reason. Everything we do occurs within the bounds of these fundamentals. Show me a patient where it’s wrong to determine what anatomy is strained or damaged and understanding the underlying mechanics is detrimental. Outside of these three decision-making principles, it is reasonable to violate the rules when necessary.

But when might it be necessary to break the rules? Well, that question can be answered by asking a few other questions about the specific patient situation. Here are a few questions I tend to ask myself about a planned treatment (nonsurgical or surgical):

- Can the patient handle it (mentally, physically)? For example, in the past I’ve chosen to perform a distal 1st metatarsal osteotomy rather than a Lapidus on patients that I felt were too anxious to handle it.

- Will they be able to comply? Locking a patient into a total contact cast on the right foot while they have to drive is a recipe for disaster.

- Will the treatment cause injury? Doing a surgery on a patient with flow-limiting peripheral arterial disease is likely to end in injury.

- Will a less complicated treatment method solve the problem? Some patients will do well with a less complex procedure. More is not always better.

I can’t help but point out that all of these questions boil down to a careful reflection on Principle 4, consider the patient (Practice Perfect 827). There’s a reason this principle immediately follows our first three!

The Case of the Lost Peroneal

Let’s take a look at an illustrative case. Some details have been changed to protect patient anonymity. This 55-year-old female with diabetes and neuropathy experienced several years of recurrent ulceration to the plantarlateral right foot after a prior infection leading to resection of the 5th metatarsal (including the base) and attempted reattachment of the peroneus brevis. Multiple nonsurgical attempts failed to fully heal the ulcer or prevent its recurrence, so surgery was in order.

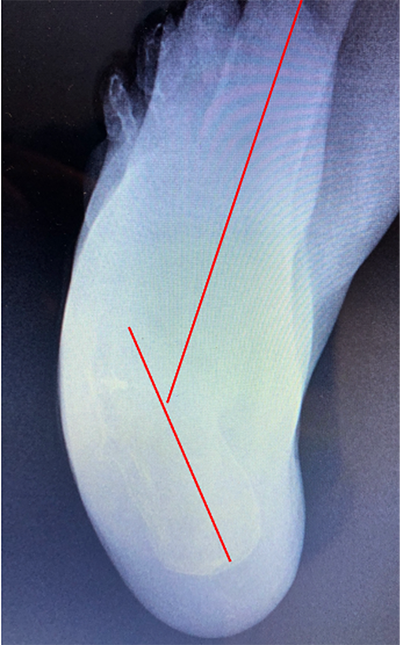

Considering our fundamental, inviolable, three rules, the damaged or strained anatomy was obvious: the skin on the plantarlateral midfoot. The underlying biomechanical cause was due originally to loss of the peroneus brevis muscle insertion with overpowering by the tibialis posterior, creating an imbalance in a varus-producing direction. Becoming increasingly rigid over time, the imbalance led to increased peak plantar pressures, breaking down the skin. Looking at the radiographs in Figure 2, coupled with the patient’s physical exam, helps us determine how to treat that underlying biomechanical abnormality. Now, if this were an acute issue, and the patient had just lost her peroneus brevis, I would have also cut the posterior tibial tendon and transferred the tibialis anterior in an attempt to prophylactically maintain balance and reduce the varus force. However, by the time I met her, that option was no longer on the table.

The procedures I chose for this patient were a triple arthrodesis, tibialis posterior tenotomy, and Achilles tendon lengthening. I carefully considered the first three rules when making my surgical decision but chose to violate one of our ten principles. Primarily, I chose not to repair the rather severe metatarsus adductus deformity, which violates Principle 5 (function follows form). I made the judgement that the heel varus was more of a factor than the forefoot adductus. I was also concerned that the patient’s tissue wouldn’t handle the amount of surgery necessary to do both the triple and a forefoot reconstruction. Essentially, I weighed the importance of Principle 5 versus Principles 3 (adjusting the forces on the hindfoot), 4 (consider the patient), 6 (fuse it if too little flexibility – this was a rigid deformity), and 9 (tendon rules – eliminating the tibialis posterior and Achilles as deforming forces). The surgical results are shown in Figures 3 and 4. The patient successfully recovered and remains ulcer-free.

Perhaps breaking the rules is really a matter of balancing the importance of one principle versus another. “Thou shalt not kill” is a principle I live by every day (even when one of my kids makes me reconsider this!), but if someone broke into my house and tried to harm my family, then, on balance, I will violate this commandment.

Perhaps breaking the rules is really a matter of balancing the importance of one principle versus another.

Similarly, in medicine and surgery we have to balance the risks with the benefits and consider if adhering rigidly to a set of rules will help or harm our patient. Podiatric medicine and surgery, like life, is about balance. Our set of ten rules will help you maintain a logical thought process but temper your decisions with a thoughtful consideration to break one rule in favor of others.

Best wishes.

Jarrod Shapiro, DPM

PRESENT Practice Perfect Editor

[email protected]

Comments

There are 0 comments for this article